The third intervention in the DASH-Sodium Trial

The effect of salt reduction on blood pressure was a contentious issue for years. That is, until the execution of the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension-Sodium Trial (DASH-Sodium). Upon dividing participants into multiple diets, and administering strictly controlled amounts of sodium, they concluded that “blood pressure can be lowered by reducing the sodium intake” from approximately 8 down to 2.3 grams per day. Moreover, greater effects were seen if people were already consuming low levels of sodium (~5 grams per day).

The effect was uniform across all groups eating a diet that is typical in the United States. However, participants in the DASH diet—containing smaller amounts of total and saturated fat and cholesterol and larger amounts of potassium, calcium, magnesium, dietary fibre, and protein than the typical diet—had discrepant results: those without hypertension did not experience significant declines in blood pressure levels (except for black participants, whose blood pressure is known to be “salt-sensitive”).

The DASH-Sodium trial was paramount to establish the current recommendations published in American and European Guidelines (a quick google search will reveal a recommended amount of 2.3 grams per day). However, the trial did not report such a thing. In reality, the reported units are sodium density: 2.3 grams per 2100 calories per day. As per the original text:

The daily sodium intake was proportionate to the total energy requirements of individual participants, so that larger or very active persons would receive more food and therefore more sodium than smaller or less active persons.

Calories, what are they good for?

What does this mean? Well. It means that if a lightly active 70 kg person required 2,100 calories to maintain their weight, they would be given approximately 3, 6, or 9 grams of salt, depending on the group they belonged to. However, a 105 kg person with the same characteristics would have received an amount equivalent to 2,600 calories: 3.7; 7,4; or 11.1 grams of salt per day. This methodology motivated a reanalysis of the data “to determine whether the strength of the relationship between Na intake and BP varied with energy intakes.” Before jumping to that study, let’s analyze another chunk of the DASH-Sodium trial.

Each participant’s energy intake was adjusted to ensure that his or her weight remained constant throughout the study.

To keep a constant weight, we need an energy balance of zero. Not even humans can disobey the first law of thermodynamics. As a result, if we want to keep our weight as is, we need to equalize the amount of food we eat (in calories) to the amount of energy we exert (also in calories). What is the rationale behind adjusting the bodyweight? We can’t tell. It was not explained by the authors and our best attempt would be an educated guess. We know, however, how they did it. They changed the total amount of calories:

Daily Intake before the study + Study Intake – Usual Energy Expenditure = 0

In other words, they changed the quantity of food people usually eat to match the difference between the usual intake and usual expenditure. The above mathematical formula has two different implications. First, there was a change in diet. Some participants started eating less once they entered the study while others starting eating more (most likely a minority). Second, the total intake used in the reanalysis is equal to the usual energy expenditure.

Daily Intake before the study + Study Intake = Usual Energy Expenditure

Total Intake = Usual Energy Expenditure

So, what happened when researchers took into account the variation by energy intake? Well, they found that “BP rose more steeply with increasing sodium at lower energy intake than at higher energy intake.” In other words, on average, larger or very active people were less sensitive to salt. Moreover, the association of sodium with systolic BP was stronger for smaller or less active people in both blacks and whites (P<0.001).

“Larger or very active”

So, were they larger or were they active? Larger implies overweight or obese patients that became obese because they maintained a caloric surplus for a significant amount of time. Some of them likely were on caloric surplus right before the start of the trial. Active, on the other hand, implies fitness and regulating adequately your caloric balance. While we never know the answer for sure, we can, again, make an educated guess by looking at Table 1 of the reanalysis:

| Category | < 2,200 Kcal | 2,200 – 3,000 Kcal | ≥3,000 Kcal | P-value |

| Normal weight | 30 (34.1%) | 32 (16.0%) | 7 (7.7%) | <0.001 |

| Overweight | 38 (43.2%) | 88 (44.0%) | 38 (41.8%) | |

| Obese | 20 (22.7%) | 80 (40.0%) | 46 (50.5%) |

A staggering 92.3% of people in the highest quartile of energy intake were overweight or obese, compared to 65.9% in the lowest quartile. Again, we can imagine that all of these people were, in practice, put on a diet as part of the participation in the study. Remarkably, experiments in obese mice have shown that going from a high-calorie diet to a normocaloric one—exactly what happened here except, of course, these are human subjects—resulted in improvements in insulin sensitivity, a potential mediator of salt sensitivity of blood pressure. Higher insulin sensitivity correlates with lower salt sensitivity to hypertension.

If my assumptions are correct, the trial design produced the following:

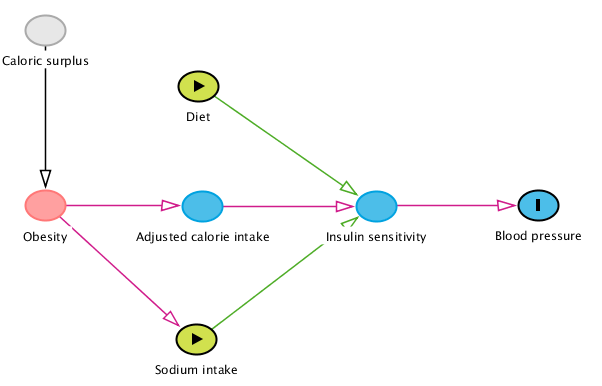

Directed Acyclic Graphs help us establish the causal assumptions from exposure (sodium intake) to the outcome (blood pressure levels). For instance, a small study showed the DASH diet improved insulin sensitivity, so we add this assumed causal relationship. We can see that an unbiased estimation would need to adjust for either obesity or the adjusted calorie intake (the difference between the amount of food people consumed before and during the study). If we look at the methods section in the original trial, we see that neither study characteristic was considered in the statistical analysis. The result is a biased estimate if we consider the absolute intake of sodium instead of sodium density, which is what current guidelines do.

Bias?

If we consider the number of sodium grams, obesity inflated the amount received by each participant. At the same time, the reduced amount of calories in the diet likely impaired the salt sensitivity of blood pressure (as shown by the 2018 reanalysis). These are opposite effects. Hence, it is not possible to establish whether the bias goes towards or away from the null.

The statistical analyses for the direct effect of sodium density and the DASH/control diet would need to control for insulin sensitivity. This is an unmeasured variable. The obvious alternative is to consider the change in energy balance from surplus to normocaloric as a third intervention, represented quantitatively by the caloric difference in the intake before and during the trial.